Author: Dave Marshall-George, Sales Director, Condair Ltd

Read the original article as published in Energy In Buildings & Industry Oct 2015

Humidity and healthcare

The Department of Health’s guidance on the design of HVAC systems for healthcare premises advises that, due to high running costs, humidity control is not required unless there is a “very specific application requirement”. However, a recently published Yale study has shown that a low indoor humidity level increases our susceptibility to airborne infections and makes us much less able to combat them.

Given that a hospital’s main purpose is to promote the health of its occupants, is maintaining humidity at an optimum level for health, a specific enough “application requirement” to make humidity control in hospitals a necessary part their HVAC design?

The recent study (1), carried by Yale University in the laboratory of Dr Akiko Iwasaki, showed that breathing air with a low humidity level reduces our immune system’s capability to fight off flu infections. The research results indicated that using humidifiers in the winter to increase the moisture content of air in occupied buildings, such as offices, schools and hospitals, is a potential strategy to reduce the seasonal impact of flu on society.

The Yale study used mice that respond to flu in a similar way to humans. The mice were infected with flu and kept in either low humidity or mid-level humidity conditions. Their physical reactions to the flu virus were then examined, including weight loss, temperature changes, their ability to clear the virus from their respiratory system and heal resultant inflammation, and ultimately their mortality rate.

The scientists found that the mice kept in low humidity (10-20%RH) suffered a much worse disease course than the mice kept in mid-level humidity (50%RH). They suffered more rapid and greater weight loss, were unable to maintain a normal body temperature and experienced a higher mortality rate.

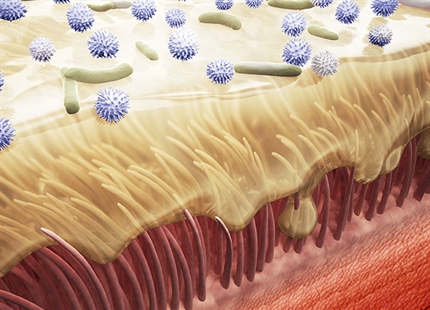

Dr Iwasaki commented, “What we found was that low humidity impairs the ability of the respiratory tract, lung and nose to get rid of the flu virus. In the airway cells, hair-like projections called cilia, are constantly moving inhaled particles along to get rid of them. However, in low humidity we found that this cilia movement, as well as particle removal, was impaired. This is particularly important for people who are very susceptible such as the very young infant or the older person over 65, as mortality from flu mostly occurs in this age group.”

The researchers also observed that low humidity reduces the ability of cells in the lungs, damaged by flu, to repair themselves. A third effect of low humidity identified in this study, was that infected cells stopped signalling for help from neighbouring cells. The ability to recruit additional immune cells to fight invading viruses or bacteria is an essential part of the body’s natural defence system, and is key to limiting disease from infections.

Commenting on the results of the study, Dr Stephanie Taylor, Infection Control Consultant at Harvard Medical School and an ASHRAE Distinguished Lecturer, said, “Dr. Iwasaki’s research shows that balanced humidification increases our overall immune defences and therefore can be applied to both viral and bacterial diseases, not limited to seasonal influenza. This study clearly shows the need to maintain indoor relative humidity at 40–60% in homes, schools, offices, hospitals, aeroplanes and all other occupied spaces.

“ASHRAE must recognize this excellent study as evidence to support a minimum RH level in occupied commercial buildings.” Dr Stephanie Taylor concludes.

This recently published study is not alone in its findings that maintaining a mid-range indoor humidity level is optimum for human health. Condair has published on its website, summaries from 25 scientific studies which took place between 1948 and 2019 relating to humidity and health. They all indicate that maintaining an indoor level of around 40-60%RH is vital for the body’s natural defence against airborne infection and in creating an atmosphere that limits the spread of airborne cross-infection.

The recent Yale study is yet further evidence for a regulatory minimum humidity level to be set for public places to reduce the impact of seasonal flu, particularly in places such as hospitals. Healthcare establishments bring infected individuals into close proximity with high risk groups, such as the elderly, very young or infirm.

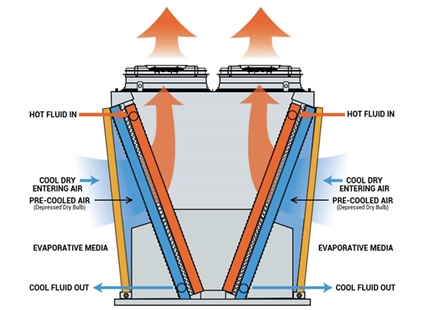

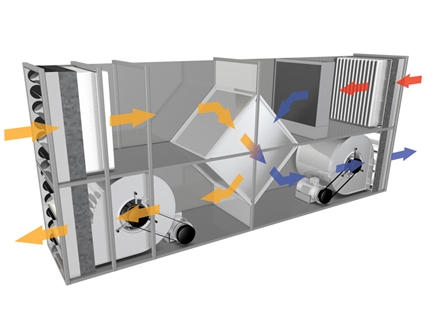

It is relatively simple to maintain a healthy indoor humidity of 40-60%RH in hospitals and other public buildings using commercial humidification systems. However, unlike temperature, humidity is not easily perceivable by occupants. This frequently results in building operators saving money by not installing, or even turning off, their humidifiers and allowing indoor humidity to drop very low in the winter.

The problem is compounded by legislation that requires building operators to reduce energy consumption. Building owners and designers are forced to minimise building services to become more efficient. However, the result is necessary services, such as humidity control, are being sacrificed at the expense of occupant health.

According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, it is estimated that 300,000 patients a year in England acquire a healthcare-associated infection (HAI), as a result of care within the NHS. This accounts for in excess of £1billion additional cost for the NHS. The most common type of healthcare-associated infections are respiratory infections, accounting for 22.8% of all HAIs.

Given the cost of airborne cross infection on the NHS, and the science showing how maintaining 40-60%RH could potentially reduce HAIs, surely it’s time that the DoH’s guidelines on the need for humidification in hospitals were reviewed? If combatting airborne respiratory infections isn’t a good enough “application requirement” for humidification of a healthcare establishment, I don’t know what is!

References: 1: Low ambient humidity impairs barrier function and innate resistance against influenza infection. PNAS May 28, 2019 116 (22) 10905-10910; first published May 13, 2019, https://www.pnas.org/content/116/22/10905. Eriko Kudo, Eric Song, Laura Yockey, Tasfia Rakib, Patrick Wong, Robert Homer, Akiko Iwasaki